*Disclaimer: The content presented in this website reflects the views of William Rouse, Student Physical Therapist and are not considered medical advice or intended to treat musculoskeletal disorders. The views expressed are not representative of the University of Findlay Physical Therapy program or the University of Findlay Athletics.

After this season ended, I took eight weeks off from even looking at a baseball. Between it being my last season, being in the midst of physical therapy summer classes, and just generally being tired of baseball, I thought it would be good for me to take a longer break than I had in years. I thought it was going to be hard not throwing, but it turns out I never really had time to throw before anyways, I had always just made time. Those eight weeks came and went pretty easily, with my clinicals and classes eating up my time. It wasn’t until the end of those weeks that I started getting the itch to throw again. Two weeks ago, I decided to start my ramp-up again. It hurt. It felt weird. It was a struggle to crack 70mph on a recovery day, when before the season, I would have had to rein in accidentally hitting 80mph. Being rusty is not a feeling I have felt since before high school. This is a point that many athletes mess up, where they feel the need to try and throw harder before their body is physically ready in order to ease their ego, or to try and alleviate their panic. At this point, trusting the process and having an objective, measurable unit to track is key.

I am approaching my ramp-up with two goals in mind: do not get hurt and be able to throw max effort 1x/week whenever my arm feels ready. This will look different for each athlete depending on their goals. Right now, where throwing hard is for fun, putting unneeded stress on my arm to meet an arbitrary timeline is not worth it. This will make my ramp-up longer than my previous ramp-ups. Last year at this time, I took on more risk with my throwing because I was chasing professional dreams. I only took 1 full week off from throwing and 1 week of recovery throws before ramping back up. That was only a 4-week ramp-up. The goal of the athlete will dictate how long the ramp-up is, but all programming should be based on something measurable. I utilize the Driveline Pulse strap and a radar gun to manage my workload and make sure I do not do too much. While these tools represent a step up from normal, arbitrary throwing progressions and cost money, I think they are well worth the investment.

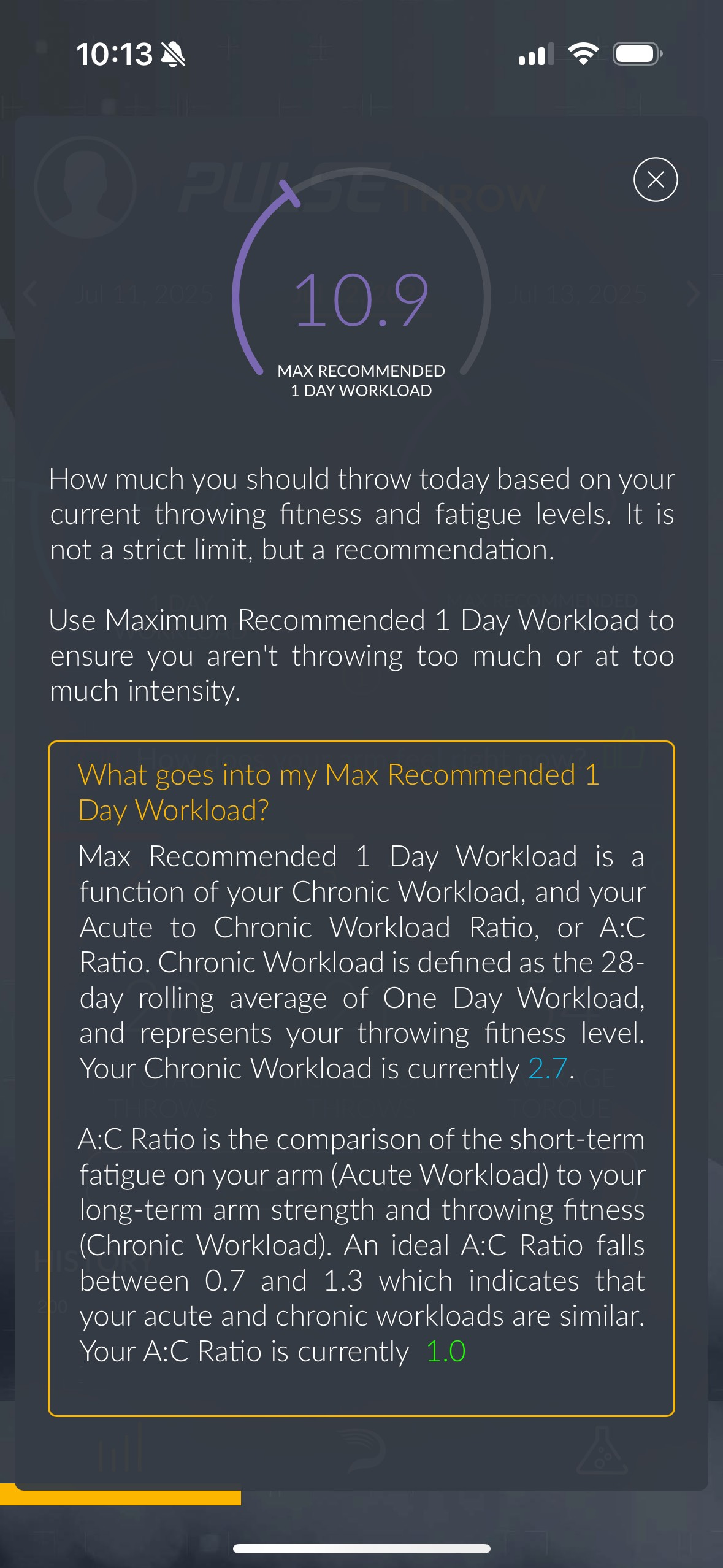

The key metrics I look at on the Pulse strap are 1-day Workload, Chronic Workload, and the acute to chronic ratio, or A:C Ratio. A description of each metric includes the following:

· The 1-day Workload is Driveline’s metric that creates a number to represent the combined intensity and volume of the day's throwing. Typically, I have set ranges I am aiming for. A recovery day for me is between 3-5 units (3 early on in the buildup, 3-5 later on), a hybrid B is 10-12, hybrid A is 13-16 units, and velo days are 18+. These goal numbers are important for managing chronic workload and A:C ratio.

· Chronic workload is the 28-day average of your 1-day workloads. This number represents your ability to handle acute levels of stress and how easily you can recover from it. A reliever with a higher chronic workload will be more able to handle pitching on back-to-back days than a reliever with a lower chronic workload. Higher levels of chronic workload are generally thought to decrease injury, but too high of a chronic workload can lead to high levels of fatigue, so there is a balance. Driveline recommends between an 8-15 chronic workload, depending on the player's role.

· Acute workload is an average of 1-day workload for the last 9 days, while chronic workload is an average of the last 28 days. Comparing these two metrics (A:C ratio) tells us if a pitcher’s most recent throwing matches their conditioning. An A:C ratio of 1 is an exact match of throwing stress, while >1 is increased acute stress, and <1 is decreased in comparison to the past month of throwing. To increase the chronic workload, you have to be in the >1 category, but research has shown that an A:C Ratio >1.3 is a higher risk for injury. Going too far below 1 leads to deconditioning, which is also a risk for injury. Because of this, Driveline recommends athletes to stay between .7-1.3 A:C Ratio.

I use the radar gun for feedback as well for managing my workload. I once heard Dean Jackson describe throwing days as a “Walk,” “Jog,” or a “Sprint” Day, and that example really stuck with me. On your recovery days, you are walking; there is no need to spike the heart rate or adrenaline. The only goal is to move around. Hybrid B or A days are jogging, where you pick up the pace but it’s not an all-out go; the focus is more mechanical or on pitch design, but intensity should not be causing high levels of fatigue. Velocity days are sprint days, where nothing is held back. My average velo day when I was playing was 89-90mph. Based on this, I set velocity parameters for each kind of day. Recovery days are 70mph and under, Hybrid B days are 80mph and lower, and velocity days are going for 90+mph, give or take 1-3mph. Tread Athletics has a really good chart breaking this down for each velocity range.

Tread Athletics Perceived Effort to Velocity Chart

For my current buildup, I am shooting for a goal of a 7-8 chronic workload by the end of the ramp-up, as I think this number will more than prep my arm to be able to handle one velo day per week early on. I am keeping the A:C ratio at a 1.1-1.3 as I need to raise my chronic workload. This will look like:

· 1-3 weeks of recovery throws with daily workloads of 3, alternating with off days. During those 2-3 weeks, as my A:C ratio stabilizes, I can either decrease the off days in between or start increasing the daily workloads to keep growing my chronic workload.

o Recovery day workload: 3 units, progressing to 3-5 units, 60-70mph

o Off day workload: 0 units

o Goal chronic workload: 3 units

· Weeks 3-6 will be slowly introducing Hybrid B and A days, keeping the A:C ratio under 1.3 and making sure to not spike my velocity before I am ready.

o Recovery day workload: 3-5 units, 65-70mph

o Hybrid B workload: 8-10, progressing to 10-12 units, 70-80mph

o Hybrid A workload: 13-15 units, 78-84mph

o Off day workload: 0 units

o Goal chronic workload: 5-6 units

· Weeks 7-8 will be dictated by where my workload is at during that time and how my arm feels, but my goal is to be able to rip my first velo day as a retired pitcher by week 8.

o Recovery day workload: 3-5 units, 65-70mph

o Hybrid B workload: 10-12 units, 75-80mph

o Hybrid A workload: 13-15 units, 80-85mph

o First Velo Day workload: 15-17 units, 85mph+

o Off day workload: 0 units

o Goal chronic workload: 7-8 units

In the past, I would map out my throwing more concretely, but now that I am done playing, I feel that it is more enjoyable to set more general parameters and throw how I want within them. This is more similar to how a relief pitcher has to manage his workload in-season. Without objective measurements, it would be nearly impossible to do safely and efficiently. Now, I can throw with the knowledge that I am as prepared for it as I can be. While it is not a requirement to use the pulse or radar gun for a proper build-up (potential article for the future), it makes the job so much easier. Even having one or the other represents a gigantic leap forward in your potential development.